Subsidies Without Delivery: Why the EU’s Hydrogen Bank Risks Undermining Itself

The European Hydrogen Bank (EHB) was launched in 2022 as the EU’s flagship subsidy instrument to kick-start a market for renewable hydrogen. Its purpose is clear:

Bridge the cost gap between renewable hydrogen (RFNBOs) and fossil alternatives.

Provide revenue certainty with 10-year fixed-price support.

De-risk early projects to accelerate Final Investment Decisions (FIDs).

The Bank runs competitive auctions where developers bid for the lowest subsidy they need (€/kg of hydrogen). Winners receive a 10-year top-up, funded through the EU’s Innovation Fund.

The idea is to make hydrogen projects bankable, create demand visibility, and signal EU commitment to decarbonising “hard-to-abate” sectors. But the early auctions show that subsidies alone don’t guarantee delivery. There have been 2 auctions so far and a one is planned for end 2025 with a budget of up to €1 billion.

How It Works

The Hydrogen Bank uses a reverse auction model: developers submit bids, the lowest asks win, and contracts secure support for a decade.

Auctions have been oversubscribed three to four times over.

Ceiling price set at €4/kg, but bids are far lower (<€0.5/kg).

Initially limited to RFNBOs, but the third auction will include low-carbon hydrogen (≥70% GHG reduction, including nuclear-powered electrolysis).

It is clear the EHB is quite good at awarding money. Whether it can create supply is another matter and yet to be seen.

The first two auctions have revealed just how strong developer interest is — and how ambitious their bids can be.

Summary of the European Hydrogen Bank’s first two auctions and upcoming 3rd, including budget, subsidies, production, and remarks.

The numbers are impressive, as shown in the above table. And looking at it closer it becomes quite evident that there is a geographical tendency. The question of where these projects are emerging and why gives way to perhaps understanding that geography is shaping outcomes as much as economics.

Geography Matters

Winners are clustered in Iberia, the Nordics, and parts of Germany and the Netherlands. Why?

Cheap renewables. Spain and Portugal have Europe’s lowest solar and wind costs. Norway and Finland have hydro and strong wind.

Grid access. Easier to connect to existing infrastructure.

Project maturity and industrial demand. Germany and the Netherlands host some of Europe’s most advanced hydrogen ecosystems. They combine mature project pipelines with strong policy backing, industrial clusters that can absorb hydrogen, and supportive port infrastructure (Rotterdam, Wilhelmshaven).

This distribution maximises cost-effectiveness, but it also exposes the Bank’s blind spot: Central and Eastern Europe are left behind despite having real industrial demand. Market creation needs both cheap supply and strong demand. Right now, it’s skewed south and north.

Europe Hydrogen Bank’s 1st auction geographical distribution of winners — heavily concentrated in Iberia, with smaller representation in Portugal and Finland.

Europe Hydrogen Bank’s 2nd auction geographical distribution of winners— Spain still leads, but Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Croatia, and Finland also appear.

The uneven spread points to a deeper issue: winning subsidies is not the same as delivering projects. That’s where the risks lie.

Where the Risks Lie — Subsidies Don’t Equal Delivery

The early auction rounds make clear that awarding subsidies and actually delivering hydrogen are two very different things. Several risks stand out and illustrate why Europe cannot equate a successful auction with a functioning market.

Execution risk. Awarding subsidies doesn’t guarantee delivery. Three winners — Spain’s Catalina (Auction 1), the Netherlands’ Zeevonk (Auction 2), and Germany’s H₂‑Hub Lubmin (Auction 2) — have already withdrawn, representing around 1.3 GW of capacity, or roughly a third of what was awarded in the first two rounds. No project has yet reached Final Investment Decision, let alone delivered hydrogen.

Concentration risk. So far, most awarded capacity clusters in Iberia and the Nordics. While this maximises cost-effectiveness thanks to cheap renewables, it sidelines demand centres in Germany, Benelux, and Central/Eastern Europe. Without a better geographic balance, hydrogen may be produced far from where it is needed most, raising transport costs and slowing adoption.

Policy drift. Expanding eligibility to “low-carbon hydrogen” risks diluting the EU’s original intent to scale RFNBOs. If nuclear or other low-carbon options crowd out renewable projects, the Bank could lose its signalling power for renewable hydrogen.

Industrial sovereignty. Extremely low €/kg bids often assume imported equipment or supply chains. That puts European electrolyser manufacturers under pressure at the very moment when industrial policy seeks to build domestic capability. If the Bank encourages dependence on external suppliers, Europe may gain volumes but lose control of its value chain.

These risks help explain why subsidy levels are so low. Developers are bidding aggressively — perhaps too aggressively — to win visibility, even if projects may not be bankable. So why are the bids so low in the first place?

Why Are Bids So Low?

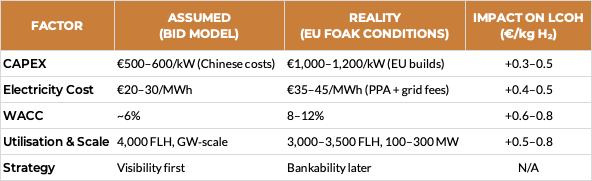

The auctions revealed strikingly low subsidy requests. Most second-auction bids came in below €0.50/kg. On paper, this implies Europe is close to competitive green hydrogen. The reality is more complicated. A side-by-side view of assumptions versus current conditions makes the gap clear:

Reality check (before subsidy):

Bid Case (optimistic): ~€2.5/kg

Reality Case (EU conditions): ~€5.0/kg

Note: The €5/kg “Reality Case” reflects mid‑range European renewable hydrogen production costs under favorable conditions. The European Hydrogen Observatory (2023) places LCOH between €6–8/kg on average, while peer‑reviewed modeling in Nature (2025) suggests €4.9–7.8/kg depending on technology. Our €5/kg benchmark is therefore an optimistic reference point.

Sensitivity Analysis — How Fragile Are LCOHs?

Looking at sensitivities shows how quickly “cheap” hydrogen becomes expensive.

Base Case (optimistic bid model):

CAPEX €600/kW, electricity €25/MWh, WACC 6%, utilisation 4,000 FLH → LCOH ≈ €2.5/kg

The reality gap is clear:

Winning bids (<€0.6/kg subsidy) assume optimistic or best-case conditions.

Realistic projects today are closer to €4–6/kg (still with favorable conditions).

No surprise somme of the early winners have already walked away.

This mismatch between assumptions and reality explains why the Commission is tightening rules for the upcoming IF25 auction.

What’s Coming Next: The IF25 Draft Auction

The recently published Draft Terms & Conditions for the IF25 Hydrogen Auction introduce several new rules that could change the game. Beyond the three headline measures, the draft sets out a broader tightening of project requirements (EC Draft Terms, 2025).

Electrolyser sourcing. At least 75% of electrolysers must now be sourced outside China, with strict limits on Chinese components. This is meant to strengthen European supply chains but may raise upfront CAPEX and slow delivery where European capacity is limited.

Cyber security. Operational control and data storage must remain in the European Economic Area. For developers with global digital platforms or tech partners, this forces a rethink of their integration strategy.

Offtake scrutiny. At financial close, at least 60% of planned output (H₂, ammonia, e-fuels) must be under binding offtake contracts. This should give buyers more certainty and lenders more confidence, but will raise the bar for developers who lack demand-side visibility.

Financial discipline. Projects must show stronger evidence of financial robustness at application stage, including clearer cost breakdowns and demonstration of equity commitments.

Timeline enforcement. The draft introduces tighter milestones and clawback provisions if projects fail to move forward, signalling Brussels wants to avoid “zombie projects” that win subsidies but never deliver.

Together, these changes show the Commission is responding to criticisms: past auctions revealed subsidy appetite but not delivery guarantees. IF25 aims to close that gap by pushing developers toward stronger supply chains, secure operations, credible demand, and stricter financial discipline. Whether this makes projects more expensive — or finally more bankable — will be the test.

The key question, then, is whether the EHB is achieving its ultimate purpose: developing a real hydrogen market.

Is the Market Really Developing?

Looking across the auctions, some things clearly work while others clearly don’t.

What’s not

No hydrogen delivered yet; projects remain years from FID.

Geographic skew undermines EU-wide strategy, concentrating benefits in a few regions.

Weak demand pull — industry remains cautious and offtake commitments scarce.

What’s working

Strong demand for subsidies — auctions are oversubscribed.

Auctions reveal theoretical floor prices, giving policymakers a signal.

“Auctions-as-a-Service” adds flexibility for member states to top up projects.

The Bank is proving good at allocating money. But a functioning hydrogen market? Not yet. And that brings us to the strategic takeaways.

Strategic Takeaways

The auctions highlight a number of lessons that policymakers and developers alike should internalise if the Hydrogen Bank is to move from paper bids to operational tonnes.

Bankability beyond subsidies. Winning an auction does not equal financing. Projects still need credible offtake agreements, grid connections, and risk-sharing structures to convince lenders. Without these, even the lowest €/kg bid can stall.

Balance geography. A healthy hydrogen market needs production close to industrial demand centres, not only where renewables are cheapest. The current skew towards Iberia and the Nordics risks creating supply–demand mismatches that add costs through transport and storage.

Resilience. Europe must weigh the value of cheap bids against the longer-term goal of industrial sovereignty. If auctions systematically reward imported electrolysers and components, the EU may undermine its own supply chain ambitions and strategic autonomy.

Focus hydrogen where it counts. Hydrogen will not decarbonise everything, everywhere. Its highest value lies in steel, chemicals, and shipping. Trying to stretch it into all sectors dilutes focus and resources.

These are not minor adjustments; they are critical to shifting the Bank from subsidy allocation to genuine market creation.

The Hydrogen Bank was set up to build a market, not just hand out subsidies. Parts of it are working — auction design, cost discovery — but delivery risks remain.

The IF25 draft shows the Commission is aware of the shortcomings. By tightening rules on electrolyser sourcing, cyber security, and offtake, it signals a shift from paper bids to real projects. Whether that shift works in practice will decide if the EHB fulfils its purpose — or becomes a subsidy machine without delivery.

The Hydrogen Bank will only succeed if today’s subsidies translate into real projects and actual hydrogen supply. At Auka Solutions, we work with developers, investors, and policymakers to bridge that gap — from techno‑economic modelling to market strategy and delivery support.